History of Poggio

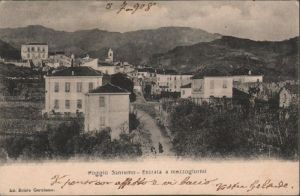

The village of Poggio, now a hamlet of the Municipality of Sanremo, is situated at an altitude of about 160 metres above sea level, in a panoramic and very sunny position on part of the hilly territory to the east of Sanremo, on the side of Armea, and to the west of Cape Verde.

The first historical news about the existence of a primitive inhabited centre in the area of Poggese date back to March 979, when the bishop of Genoa Teodolfo, persuaded perhaps by the remarkable productive and quantitative level reached by his lands located in the Sanremo territory, decided to accept a petition of a group of thirty-nine local settlers, with which the latter asked the prelate for the concession in emphyteusis of two mansi, i.e. vast plots of arable land, situated in the Sanremo district, of which the first, which included a large portion of hilly and mountainous land with land, reeds, olive groves, willow groves, fields and pastures and a wide availability of water resources, extended from the top of Monte Bignone to Capo Pino, located in the south-western part of the Sanremo territory, including, among other places, that of Poggio, where there probably already existed a primitive inhabited centre consisting of a small community of farmers and shepherds.

The first historical news about the existence of a primitive inhabited centre in the area of Poggese date back to March 979, when the bishop of Genoa Teodolfo, persuaded perhaps by the remarkable productive and quantitative level reached by his lands located in the Sanremo territory, decided to accept a petition of a group of thirty-nine local settlers, with which the latter asked the prelate for the concession in emphyteusis of two mansi, i.e. vast plots of arable land, situated in the Sanremo district, of which the first, which included a large portion of hilly and mountainous land with land, reeds, olive groves, willow groves, fields and pastures and a wide availability of water resources, extended from the top of Monte Bignone to Capo Pino, located in the south-western part of the Sanremo territory, including, among other places, that of Poggio, where there probably already existed a primitive inhabited centre consisting of a small community of farmers and shepherds.

The first historically certain proof of the existence of Poggio dates back to the middle of the 11th century, when the village was part of the great feud of the bishop of Genoa, then called Curia Sancti Romuli, whose borders ran east with the Armea river, to the west were marked by the Capo Pino, then climbing along the ridge up to the summit of Monte Bignone, then descending to the Ghimbegna Pass, climbing up to Monte Arpicella, then following the dyspluvial between the Argentina and Armea Valleys to finally close in on the stream that crosses the latter valley.

The Genoese bishop also owned other lands outside the above mentioned borders and located in the territory of Taggia.

The curia thus circumscribed included the inhabited areas of Sanremo (Sancti Romuli) and Ceriana (Celiane), while the relative districts were separated by mountain expanses of woods and meadows which, by ancient custom, were left by the feudal lord for collective use.

Even to the east, towards the territory of Bussana (Buzane), there was an uncultivated area made up of the mountain ridge that from Mount Bignone descended to the sea between the streams of Armea and San Martino, and whose summit corresponded in fact with the current Mount Colma, while the slope to the sea developed in the central part of the valley for a long time called Val d'Olivi, perhaps due to the name of mons Vallis, which represented its ancient name.  And it was precisely because of the possession of this hill, Mount de Valle, the ridge between Mount Bignone and Cape Verde, that bitter disputes between the men of Sanremo and those of Ceriana took place in the first half of the 12th century, so much so that at the beginning of 1143, the Cerianesi returned to the judgement of the Archbishop of Genoa, Siro II, on the occasion of the solemn oath of loyalty given by the people and consuls of the village of Valle Armea to the Genoese prelate. The archbishop then divided the disputed mountain into three parts, one of which, to the north, was granted as a feud to the community of Ceriana, the second, situated to the south-west, was attributed to the Sanremesi, so much so that it remained for centuries among the bandits of the Matuzian community, and the third part, which extended to the south-east towards Bussana and the sea, was also assigned to the Sanremesi with a perpetual lease deed as it is transcribed in the Curiae registrum under the date of 1 August 1154.

And it was precisely because of the possession of this hill, Mount de Valle, the ridge between Mount Bignone and Cape Verde, that bitter disputes between the men of Sanremo and those of Ceriana took place in the first half of the 12th century, so much so that at the beginning of 1143, the Cerianesi returned to the judgement of the Archbishop of Genoa, Siro II, on the occasion of the solemn oath of loyalty given by the people and consuls of the village of Valle Armea to the Genoese prelate. The archbishop then divided the disputed mountain into three parts, one of which, to the north, was granted as a feud to the community of Ceriana, the second, situated to the south-west, was attributed to the Sanremesi, so much so that it remained for centuries among the bandits of the Matuzian community, and the third part, which extended to the south-east towards Bussana and the sea, was also assigned to the Sanremesi with a perpetual lease deed as it is transcribed in the Curiae registrum under the date of 1 August 1154.

This last territory coincided exactly with what would become the jurisdiction of the fractional community of Poggio, whose location outside the Sanremese area is confirmed by the toponym of San Martino, situated to the east of the Matutian city at the classic distance of one Roman mile from the centre, where the Via Aurelia crossed the stream of the same name and where it seems there was an oratory dedicated to this saint to whom it was customary to entrust the protection of the limits of jurisdiction of the urban areas.

As far as the state of economic availability of the area is concerned, it is clear that, in the above mentioned deed, neither inhabitants nor inhabited areas were mentioned, nor the presence of chapels, mills or other production plants, besides the very significant detail that, among the agricultural products that the inhabitants of the territory of Poggese should have paid to the Archbishop's Curia as taxes, neither oil nor olives were mentioned. From these elements it can therefore be deduced that, towards the middle of the 12th century, there was only a valley in the area of Poggese that was not yet cemented by walls or glazed with greenhouses and not yet covered even by that thick silvery blanket of olive trees, which continues to give it its name, even if it is now improperly named, but it must have been presumably the flowering place of a vast Mediterranean scrub, from which, since 1154, the scent of broom had spread intensely.

As far as the state of economic availability of the area is concerned, it is clear that, in the above mentioned deed, neither inhabitants nor inhabited areas were mentioned, nor the presence of chapels, mills or other production plants, besides the very significant detail that, among the agricultural products that the inhabitants of the territory of Poggese should have paid to the Archbishop's Curia as taxes, neither oil nor olives were mentioned. From these elements it can therefore be deduced that, towards the middle of the 12th century, there was only a valley in the area of Poggese that was not yet cemented by walls or glazed with greenhouses and not yet covered even by that thick silvery blanket of olive trees, which continues to give it its name, even if it is now improperly named, but it must have been presumably the flowering place of a vast Mediterranean scrub, from which, since 1154, the scent of broom had spread intensely.

The commitment of the young people who were about to carry out the task of transforming the valley and the opposite side that descended to the Armea, was therefore summarised in the diplomatic formula of two words with which the Consuls of Sanremo took on the burden: colere et meliorare, that is, to cultivate and improve, an essential prerequisite for the foundation of a real inhabited centre. Behind the conventional words of the official deed was therefore underlying a project for the colonisation of the Poggese district, where, even if it can be excluded a priori, on the basis of the current state of the documentation, the existence of an older built up nucleus on the site, it is however certain that at the time of the stipulation of the deed of foundation of the village, the area was certainly depopulated and abandoned after the destructive Saracen raids of the 10th century.

On the basis of the above mentioned elements, it is therefore possible to date back to around 1154 the foundation, or refounding, of "Villa Podii Sancti Romuli" by the community of Sanremo, which had woven close legal and administrative ties with Poggio starting from the filiation of the local church of Santa Margherita as a rectory dependent on the Sanremo matrix of San Siro.

On the basis of the above mentioned elements, it is therefore possible to date back to around 1154 the foundation, or refounding, of "Villa Podii Sancti Romuli" by the community of Sanremo, which had woven close legal and administrative ties with Poggio starting from the filiation of the local church of Santa Margherita as a rectory dependent on the Sanremo matrix of San Siro.

From the state of the situation in the centuries of the Late Middle Ages there emerges a deep analogy between Poggio and the almost symmetrical village of Colla (today's Coldirodi), which is not limited to the evidence of topological correspondences, but is attested by the equation between the lands west of the moat of the Mouth, where the Colla is located, and those to the east of the moat of Val d'Olivi, where the centre of Poggio is located, in the deeds of transfer of the Sanremo feud from the Archbishop of Genoa to the Doria and De Mari families, and from them to the Republic, with equal obligations of the settlers towards the feudatories. These obligations consisted in particular in the tribute of a fourteenth of the blade (wheat, barley, broad beans), and an eighth of the wine, which were, moreover, very favourable when compared to those of other emphyteustic concessions in Sanremo itself.

The foundation of Poggio can also be linked to an organic programme of agricultural development, which also included the formation of new villages, implemented towards the middle of the 12th century, connected in all probability to a substantial demographic increase and undoubtedly linked to new equilibriums of a more strictly economic nature favoured by the mercantile and maritime development of the town of Matuzzo in a spirit of renewed commercial impetus that would characterise the future development of the local economy.

The birth of the village of Poggio also posed serious problems of peaceful coexistence with neighbouring communities, such as that of Bussana, so much so that the Archbishop of Genoa, Ugo, who, holding court in Sanremo in December 1164, confirmed his rights as feudal lord over the whole territory extending from Armea to Sanremo, eventually had to intervene, that is from Armea to San Martino, stigmatizing at the same time the claims and protests made by the men of Bussana, guilty of having reacted to the fact that a new community came to gravitate on the lower Armea valley and on the brave vegetable garden in which the Bussaneses had farms even to the west of what had now become the shore of the stream.  Compared to the morphological structure of the territory, the location of the new village appeared to be in a particularly favourable position, situated in a natural hillock situated high up, but covered with a view from the sea and therefore in good defensive conditions against possible maritime aggressions. The village was also able to control - and this condition would not take long to produce beneficial effects in the following centuries characterised by numerous wars and deadly plagues - the road that connected the two major centres of the district and that continued upstream towards Baiardo and Castelfranco.

Compared to the morphological structure of the territory, the location of the new village appeared to be in a particularly favourable position, situated in a natural hillock situated high up, but covered with a view from the sea and therefore in good defensive conditions against possible maritime aggressions. The village was also able to control - and this condition would not take long to produce beneficial effects in the following centuries characterised by numerous wars and deadly plagues - the road that connected the two major centres of the district and that continued upstream towards Baiardo and Castelfranco.

The first hovels that were built perched on the hill, although rather rudimentary, had to be characterized by some articulation of spaces, between those intended for very modest living and those of rustic use such as stables, barns and cellars.

It is, however, very unlikely that under the successive building sedimentation there will remain any remains of those primitive dwellings, as only a few centuries later more advanced building methods would have guaranteed such poor houses any chance of lasting.  In the general layout of the present day town, however, it is still possible to read the morphological basis of the primitive settlement, the matrix of the subsequent additions, so much so that an intentional rationality of planning, particularly interesting in the 12th century, can still be recognised, which was to be taken up in the numerous foundations of new urban centres in the course of the following century.

In the general layout of the present day town, however, it is still possible to read the morphological basis of the primitive settlement, the matrix of the subsequent additions, so much so that an intentional rationality of planning, particularly interesting in the 12th century, can still be recognised, which was to be taken up in the numerous foundations of new urban centres in the course of the following century.

Even the present parish church preserves the orientation from west to east of the primitive church, as does the access from a churchyard square that in the northern part expanded towards the cemetery, where the road to Ceriana bent sharply towards the mountain. From this crucial point the structure of the village was articulated with a twofold trend: upstream the Castello district aligns its houses along alleys parallel to the main road, while downstream, along the sides of the church, two rectilinear carruggi delimit as many closed districts with the houses welded in the centre in a double row, wall against wall, forming a continuous front that overlooks the vineyards below and has been tightened according to a clear intention of defensive nature.

Since its foundation, however, the village must have been strongly influenced by a series of cultural and religious suggestions, as can be seen from the urban structure of the "sub-church" districts marked by some symbolic references which, in an ecclesiastical feud, represented an earthly authority, as well as guarantors of a transcendent sense of existence, documented by the death experienced as a daily event expressed in the churchyard in the centre of the village united without solution of continuity with the cemetery, by the social solidarity of the relatives gathered in the closed environments of the districts, by the resources of the cultivated land that can be reached through the margins built with descending archivolts and by the external threats faced by the permanent garrison of the inhabitants in the houses side by side in the stretch of the walls between the towers and the ramparts.

The political change that had taken place in the middle of the 14th century with the cession of the territory of the ancient Sanremo curia to the Republic of Genoa had not only constituted a change of feudal lord, but the conclusion of a long and contrasting process of emancipation, which cannot be separated from a phase of considerable and impetuous economic growth.

In fact, the agreements of 1358 included, on the part of the communities of Sanremo and Ceriana, payments in money which also formally sanctioned the redemption from the heavy feudal contributions. The men of Poggio, who had certainly contributed for their part to the stipulation of the agreements, had to have obtained at least the first recognition of the longed-for independence of their village. The contemporary growth of the urban structure of the village experienced a period of expansion that ended, perhaps around the end of the 15th century, with the enlargement of the parish church of Santa Margherita.

Meanwhile the inhabitants of Poggio, also because of their distance from Sanremo and the difficulties they encountered in enjoying the spiritual advantages of the Matuzian parish church of San Siro, had asked in 1452 the bishop of Albenga (on which the territory of Sanremo depended at the time) for permission to detach their branch church of Santa Margherita from that of San Siro.

On the 9th November of the same year, having received the consent to the splitting by the San Siro provost, the church of Santa Margherita was elevated to parish dignity, at the same time obtaining the assignment of the tithes paid by the inhabitants of Poggio, with the obligation for the consuls of the hamlet to pay, by way of recognition, seven florins to the former mother church, while the church in Poggese, which was enlarged and rebuilt on the occasion of its elevation as a parish, was to be solemnly consecrated on 12 October 1488 by the Bishop of Albenga Leonardo Marchese. In the meantime the population of Poggio, which in 1511 counted about 400-450 souls (112 families), had risen in 1664 to 726 inhabitants (194 families), and finally in the 18th century it was about 900 inhabitants.

The countryside surrounding the village of Poggese produced considerable quantities of olive oil, wine, figs and almonds, while palms, lemons and vegetables were also cultivated.

A fair export of oil, lemons, palms and wine fed modest commercial activities with Sanremo, but the economy was still limited to a strictly local area.

The subsequent development of the town during the 16th century led to the construction of a nucleus of houses in the lower part of the insellatura, along the road leading to Sanremo. Towards the middle of the sixteenth century the village had meanwhile been invaded by the threat of the Barbary pirates, who in 1561 landed on the sandy shore of San Martino, but were put to flight by the balls of the existing bombardment in the castle of the Matuziana town. The effectiveness of the defensive action then induced the Sanremo authorities to buy two more bombards, which were placed in Cape Nero and Cape Verde, but also the population of Poggio asked for more adequate protection in view of possible assaults by Algerian corsairs. While the representatives of the Villa requested to close all the existing openings in the continuous row of houses that delimited the external perimeter of the village, with the exception of some constantly guarded doors, the inhabitants of the group of houses below the village in the locality of Poxetto, all belonging to the Moraglia families, asked permission to erect a tower against the "infidels".

On 31 August 1561 the deed of transfer of the land was stipulated and the tower was then completed the following year, after financial difficulties had forced the promoters of the work to request the intervention of the Genoese authorities. The works for the consolidation and completion of the walls were also completed thanks to the help of the Republic and after the collection of a tax charged to the population, to the profound satisfaction of the inhabitants, who had already suffered some ambushes and kidnappings by corsairs.

On 31 August 1561 the deed of transfer of the land was stipulated and the tower was then completed the following year, after financial difficulties had forced the promoters of the work to request the intervention of the Genoese authorities. The works for the consolidation and completion of the walls were also completed thanks to the help of the Republic and after the collection of a tax charged to the population, to the profound satisfaction of the inhabitants, who had already suffered some ambushes and kidnappings by corsairs.

Despite the fact that the latter had continued undaunted to carry out raids and raids on the coast of western Liguria, the chronicles of the time no longer mention Villa Podii among the towns attacked by the Barbareschi.

In the following decades Poggio's dependence on the chief town was accentuated, as is attested by the decision taken by the Parliament of Sanremo in 1595, following the invalidation of the election of the consuls of Colla, on the basis of which it was decreed that the election of the consuls of the villas of Colla and Poggio by the inhabitants of the two Sanremo hamlets would no longer be allowed without the intervention of the podestà and the priors of the Matuziana community.

This decision, which unequivocally reaffirmed the dependence of the two villas on the capital, was part of a complex of administrative regulations aimed at improving and rationalising the functioning of the Sanremo government, so much so that shortly afterwards it was also established that a practice could not be proposed to Parliament before it was submitted to the Council.

In the course of the modern age the custom of holding elections for local consuls in the presence of the podestà of Sanremo on the occasion of the patronal feast of Saint Margherita on 20th July was also established, while the people of Poggio benefited from the charitable activities carried out by the altar companies erected on the altars of the parish church, in which many of the inhabitants of the village also militated, among whom there were also numerous priests originating from families of Poggio who, thanks to the favourable trend of commercial activities, enjoyed a fair economic wealth.

During the subsequent war between Genoa and the Savoys, which broke out in 1625, the town of Poggio was also involved, albeit indirectly, in the conflict, so much so that on 3 August 1935 the Sanremo authorities, fearing an attack by the French by sea, forced the inhabitants of Poggio and Collantini to retreat within the walls of the village during the night, taking their supplies with them, with the sole exception of the mill workers and farmers who irrigated the fields to prevent the citrus fruit crops from being abandoned.

During the subsequent war between Genoa and the Savoys, which broke out in 1625, the town of Poggio was also involved, albeit indirectly, in the conflict, so much so that on 3 August 1935 the Sanremo authorities, fearing an attack by the French by sea, forced the inhabitants of Poggio and Collantini to retreat within the walls of the village during the night, taking their supplies with them, with the sole exception of the mill workers and farmers who irrigated the fields to prevent the citrus fruit crops from being abandoned.

After alternate events, the village returned to participate actively in the historical events of Sanremo during the revolution of 1753, when, together with Verezzo, the hamlet of Matuzzo openly sided against the Republic. The firm reaction of the Genoese authorities was not long in coming and General Pinelli severely punished the rebel village with the confiscation of the cattle and the payment of a sum of money equal to 1591 lire, obtained by force from the 768 inhabitants. During the days of the revolt, the population, encouraged by four men who had come from Sanremo on purpose, had opposed the advance of the grenadiers who were going to occupy Ceriana. After the very hard repression carried out by the Genoese troops, the response of the Poggesi, like the inhabitants of Verezzo, was passive resistance, so much so that when, in 1755, after many difficulties, one of the consuls was elected, he immediately went to the outcast comrades who had taken refuge in Perinaldo and was arrested by the Genoese police on his return to Poggio.

After the birth of the Ligurian Republic in 1797, the new Municipality of Sanremo decided to replace the two consuls, who were entrusted with the administration of Poggio and Verezzo, with two inspectors, while the town became part first of the Palm District and then of the Olive Jurisdiction with Sanremo as its main town.

I n 1805 the village was annexed, together with the rest of Liguria, to the French Empire under the administration of the Maritime Alps Department, with Nice as its capital, after the fall of Napoleon and the decisions of the Congress of Vienna, under the jurisdiction of the Kingdom of Sardinia, which had incorporated the territory of the deceased Republic of Genoa.

n 1805 the village was annexed, together with the rest of Liguria, to the French Empire under the administration of the Maritime Alps Department, with Nice as its capital, after the fall of Napoleon and the decisions of the Congress of Vienna, under the jurisdiction of the Kingdom of Sardinia, which had incorporated the territory of the deceased Republic of Genoa.

About fifteen years later, in 1831, Poggio, together with many other towns in the Matuan district, including Sanremo itself, left the Diocese of Albenga and entered the Diocese of Ventimiglia in execution of the Papal Bull issued by Pope Gregory XVI on 20th June of that year.

At the beginning of September 1837 the village was hit by a terrible cholera epidemic, which, after having claimed many victims in Sanremo, had gradually moved towards the hamlet of Sanremo, where it would have affected many inhabitants of the village.

Between 1844 and 1878 the mayor of Sanremo, Count Stefano Roverizio di Roccasterone, promoted several important public works, some of which also involved Poggio, where the carriage road that leads from the village to the Sanctuary of the Madonna della Guardia was laid out.

In 1855 the new mayor Antonio Bottini had in the meantime opened the road to Poggio, which would then be continued to Ceriana.

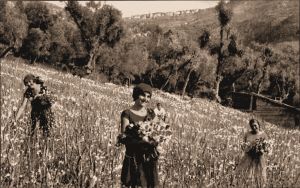

In 1860, following the transfer of the Nizzardo to France, Poggio, again as a hamlet of Sanremo, became part of the new province of Porto Maurizio. In the second half of the nineteenth century floriculture began to spread in the territory of Poggio, which included among its pioneers the doctor Costanzo Aicardi, who founded the first floricultural farm in the village along the slope leading to the village. Under the administration of the mayor Bartolomeo Asquasciati the water pipeline was then built between 1878 and 1879, while, during the construction of the new Matuziano aqueduct by the Marsaglia company, a large reservoir was built around 1884 to collect water near the town.

In the second half of the nineteenth century floriculture began to spread in the territory of Poggio, which included among its pioneers the doctor Costanzo Aicardi, who founded the first floricultural farm in the village along the slope leading to the village. Under the administration of the mayor Bartolomeo Asquasciati the water pipeline was then built between 1878 and 1879, while, during the construction of the new Matuziano aqueduct by the Marsaglia company, a large reservoir was built around 1884 to collect water near the town.

The subsequent earthquake in February 1887 caused only slight damage to some buildings without fortunately causing casualties, apart from the roof of the parish church which was completely ruined by the consequences of the earthquake.

After the years of the First World War, during which several soldiers of Poggese origin fell at the front, the local economy, now largely based on floricultural activities, benefited considerably from the opening, in September 1922, of the new Sanremo flower market, where floriculturists from Poggese were able to market their products more easily than they could at the Ospedaletti market, which until then was the only one working in the Matuziano area.

During the following period of the Fascist regime, the new school building in the town was built, while economic activities continued to expand until the outbreak of the Second World War, when the town first had to face the brief conflict with France in June 1940 and then, from September 1943, the consequences of the war between the Germans and the partisans, which directly affected the territory of Poggese.

One of the most important actions carried out by the partisan forces took place on 26 August 1944, when a squad of the second detachment of the IV Brigade "Elsio Guarrini", taking advantage of the stop of a German truck in the village square, fired a burst of machine guns on the load of the vehicle, consisting of fifteen drums of petrol, setting fire to it, while at the beginning of the following September a Patriotic Action Squad (SAP) was established in the village, which would have actively collaborated in the War of Liberation.

At the beginning of November 1944, the CLN of Poggio was set up, formed by the communist Ernesto Boiolo, as president, and the independents Nino Ghersi, Antonio Mancini and the socialist Emilio Moraglia as members of the Committee.

However, the saddest episode of the entire resistance period took place on 24 November 1944, when the Nazi-Fascists, after having carried out a massive roundup in the village, shot ten civilians in retaliation, which would be followed, on 22 April 1945, by the shooting of the Milanese Gualtiero Zanderighi; the names of these fallen soldiers are today remembered on a memorial plaque located in Piazza dei Martiri.

After the end of the war the town lived a period of development of its social and economic activities, with renewed attention from the Sanremo municipal authorities, who promoted the construction of the new schools of Poggio, inaugurated in December 1949, and the building of "Casa Serena", a modern structure situated on the hill of the village, destined to welcome the pensioners of the Inps and officially inaugurated in April 1969 in the presence of the mayor of Sanremo Francesco Viale.

Nowadays the main economic resource of Poggio is the floriculture with numerous cultivations in the open air and especially in the greenhouse that surround the village, where they have almost completely replaced the ancient palm and olive groves, which still survive, although reduced, along the road to Ceriana and the Sanctuary of the Madonna della Guardia.

There are also still some vineyards, from which the renowned "white" of Poggio is obtained, a Vermentino wine of ancient tradition obtained from a vine of Iberian origin present in the area between Bussana and Dolceacqua from the 15th century with maximum diffusion until the 18th century, but which today is very difficult to find on the market so that it can be tasted only at the producers or in some restaurants in the area, considering the fact that the modest production of the Poggio vineyards is mainly for family use.

(sources: text by Andrea Gandolfo; personal and web archive images)