History of Bussana

The oldest evidence of human presence in the territory of Bussana can be traced back to an ancient phase of the Middle Palaeolithic (Würm I) between about 80,000 and 60,000 years ago.

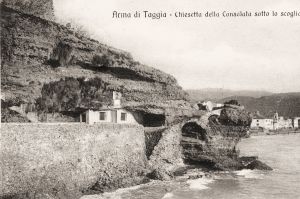

The main prehistoric site that documents this human presence is the Grotta della Madonna dell'Arma, also known as Nostra Signora Annunziata dell'Alma, consisting of a north-south oriented gallery with a total length of about 55 metres with a development of narrow passages that exceed one hundred metres and a current surface area of about 350 square metres, situated on the small promontory that represents the extreme southern tip of the "Castelletti" hill.

The main prehistoric site that documents this human presence is the Grotta della Madonna dell'Arma, also known as Nostra Signora Annunziata dell'Alma, consisting of a north-south oriented gallery with a total length of about 55 metres with a development of narrow passages that exceed one hundred metres and a current surface area of about 350 square metres, situated on the small promontory that represents the extreme southern tip of the "Castelletti" hill.

The history of Bussana, from the Palaeolithic to the pre-Roman and Roman era up to the barbarian invasions, follows equally that of Sanremo. (c.f.r History of Sanremo parts 1, 2, 3)

After the final defeat of the Saracens between 975 and 980 there was a general resumption of economic activities together with a lively desire for peace and mutual help that led, around the year 1000, to the need to permanently own the land to devote themselves to sheep farming and agriculture.

So in 979 twenty-nine families living in the area of Sanremo and Bussana asked and obtained from the Bishop of Genoa Teodolfo the concession to rent a large cultivable area, after which the population of Bussana increased considerably and the first houses were built, not scattered and hidden in the Armea Valley, but towards the top of a rocky hill, where the feudal lord of the area, a representative of the Counts of Ventimiglia, had erected a castle around the middle of the 11th century, when the number of houses built around the manor grew and the inhabitants of the village began to live together in close union also to defend themselves more easily from any external attacks.

The first document in which the name of Buzana is attested dates back to 1140, when the Municipality of Genoa promised the Marquises of Savona half of the village as a reward for the help given in the war against the Counts of Ventimiglia. Thirteen years later we find another mention of the village in the proxy granted by the Bishop of Albenga to Anselmo de Quadraginta for the collection of tithes in the territory under the jurisdiction of the prelate ingauno, who had difficulty in collecting taxes in the most distant and remote towns such as Bussana, over which Anselmo did not extend his control and the village remained in the possession of the Counts of Ventimiglia.

The first document in which the name of Buzana is attested dates back to 1140, when the Municipality of Genoa promised the Marquises of Savona half of the village as a reward for the help given in the war against the Counts of Ventimiglia. Thirteen years later we find another mention of the village in the proxy granted by the Bishop of Albenga to Anselmo de Quadraginta for the collection of tithes in the territory under the jurisdiction of the prelate ingauno, who had difficulty in collecting taxes in the most distant and remote towns such as Bussana, over which Anselmo did not extend his control and the village remained in the possession of the Counts of Ventimiglia.

Towards the middle of the thirteenth century the heirs of the counts, no longer able to exercise their effective dominion over the many countries of the extreme western Liguria still formally in their possession, decided to sell their rights over these villages to the Republic of Genoa, which aimed to extend its jurisdiction also over this strip of Ligurian territory.

On 24 November 1259 Count Oberto's daughter, Veirana, sold her share of Bussana and Arma to the Genoese Municipality, while two months later, on 21 February 1260, her brother Bonifacio, too, sold his share of the inheritance, consisting of the other half of Bussana and Arma and the villages of Triora and Castelvittorio, to the Genoese nobleman Ianella Avvocato for a total sum of 3000 lire, which would then be sold by Avvocato to the Municipality of Genoa on 4 March 1261. With this historic sale the feudal period of the Counts of Ventimiglia ended for Bussana and the period of belonging to the Republic of Genoa began, to which it would remain linked both politically and administratively until the end of the 18th century. During the 13th century the coastal area between the Armea torrent and the Grotta dell'Arma gradually repopulated, as can be seen from the oaths of allegiance to the Municipality of Genoa in 1260-61, thanks also to the particular fertility of these lands, the most ubiquitous in the whole Bussano area, which were irrigated with water from the stream channelled into special beodi, which, in addition to irrigating the vegetable gardens, was used to drive the wheels of the wheat mills and the first existing olive presses along the banks of the Armea.

During the 13th century the coastal area between the Armea torrent and the Grotta dell'Arma gradually repopulated, as can be seen from the oaths of allegiance to the Municipality of Genoa in 1260-61, thanks also to the particular fertility of these lands, the most ubiquitous in the whole Bussano area, which were irrigated with water from the stream channelled into special beodi, which, in addition to irrigating the vegetable gardens, was used to drive the wheels of the wheat mills and the first existing olive presses along the banks of the Armea.

This return of the Bussanesi to the coastal strip was, however, short-lived because already in 1270 the Genoese military forces, during a series of internal struggles between opposing factions, once again brought terror and death among those inhabitants accused of having hosted some men considered rebels by the government of the Republic, so that the Armenian coast became practically uninhabited again.

Then the development of the village upwards resumed, but the abandonment of the coast became the object of attention of the inhabitants of Taggia, who aspired to extend their dominion in that area leading to new quarrels and disputes with the Bussanesi.

Then the development of the village upwards resumed, but the abandonment of the coast became the object of attention of the inhabitants of Taggia, who aspired to extend their dominion in that area leading to new quarrels and disputes with the Bussanesi.

During an attempt to make peace between Bussana and Taggia in 1357, the people, in a solemn assembly, decided to merge the two countries into a single community, whose institution was approved almost unanimously also because of the absence of many Bussanese.

The new administrative entity was then provided with special Statutes, which, already approved for Taggia in 1381, were adapted to the new requirements. On the basis of these provisions, the Municipality would be governed by four Elders (three from Taggia and one from Bussana), who, together with the other city authorities, formed the Municipal Council, presided over by a Genoese podestà, who was also entrusted, as in the other centres, with the administration of justice.

The new administrative entity was then provided with special Statutes, which, already approved for Taggia in 1381, were adapted to the new requirements. On the basis of these provisions, the Municipality would be governed by four Elders (three from Taggia and one from Bussana), who, together with the other city authorities, formed the Municipal Council, presided over by a Genoese podestà, who was also entrusted, as in the other centres, with the administration of justice.

However, after about seventy years of union with Taggia, the Bussanesi eventually asked for the separation of the two municipalities from the Genoese government, which granted it in 1428.

The town of Bussana Genova was granted simple administrative rules, mainly concerning agriculture and pasture, which also provided for financial penalties for offenders, while the population elected four Elders every year who applied what had been established by Parliament, a sort of meeting of the heads of families, and two consuls were instead in charge of administering justice by imposing the penalties provided for by the laws in force.

During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries there was a substantial demographic increase with the consequent need to build new houses and new roads to meet the increased commercial and economic needs.

« From the land registers and censuses of the goods of the time, it is also possible to obtain the types of products most cultivated and consumed by the Bussanesi, among which wheat, barley and rye stood out, while some mills, two in the Lunaire region and two others in the region still called "Molini", provided for the transformation of wheat into flour. Even the production of bread, made by special millers, was subject to strict control by the municipal authorities, which laid down precise rules for the good progress of the production of this product which is the basis of the population's diet. Very important was also the cultivation of fig trees, widespread in all the countryside and protected by the municipal laws of the country, whose various qualities allowed the presence of the fresh fruit for several months. The surplus product was dried on racks, the so-called "vizze", and stored until the winter-spring period in the "garocci", wooden containers built to transport the grapes and used only during the harvest days and then available for other uses during the winter months. There were few legumes and vegetables because of the difficulties of summer watering, more widespread were the cultivations of chickpeas, broad beans, peas, cabbage, turnips, pumpkins, chard, garlic, onions, aubergines and artichokes, particularly renowned was the local wine, aromatic and alcoholic, the production of chestnuts was insignificant, while more abundant was that of olives, from which a fair amount of oil was obtained, just enough for the needs of the inhabitants of the village. According to the data of the census carried out by the Genoese authorities in 1531, 91 men between 17 and 70 years of age lived in Bussana, all of them engaged in agriculture, while the total population was one hundred families with 370 people, who owned 15 oxen and 70 goats, with the harvest of wheat and other fodder that could be enough for three months, wine for six, oil for four and figs for six. The following land registers are rich in other indications regarding place names, people and products, but poor in data regarding the quantity of the products themselves, from which it can be deduced that the productive situation of the economy of Bussano has remained practically unchanged for centuries, increasing slightly with the population, which was therefore always forced to devote itself to rural activities in order to guarantee itself a modest and honest survival ».

In the 17th century the socio-economic situation of the town improved further, as attested by the demographic increase and the contemporary building development, due both to the increase in the number of houses and the construction of a new oratory and the enlargement and renovation of the parish church. This improvement is also confirmed by the foundation of numerous chaplaincies with bequests in favour of heirs from the wealthiest families of the village, such as the Torre, Soleri, Cappone, De Bernardis and Bianchi.

However, in that period there were also raids and pillages by gangs of pirates, especially barbarians, who landed almost annually on our coasts during the 16th century, capturing hundreds of prisoners, plundering houses and destroying everything in their path. Fortunately, the town of Bussana was saved from this violence thanks to its lack of means, furniture and food, as well as its good natural and human defences, even if its countryside was sometimes damaged by barbarian raids, for which the quadrangular fortress of Bussana was also built in 1565, but it remained unused in the following centuries because of the end of the pirates' attacks.

However, in that period there were also raids and pillages by gangs of pirates, especially barbarians, who landed almost annually on our coasts during the 16th century, capturing hundreds of prisoners, plundering houses and destroying everything in their path. Fortunately, the town of Bussana was saved from this violence thanks to its lack of means, furniture and food, as well as its good natural and human defences, even if its countryside was sometimes damaged by barbarian raids, for which the quadrangular fortress of Bussana was also built in 1565, but it remained unused in the following centuries because of the end of the pirates' attacks.

During the seventeenth century the territory of Bussana also had to suffer the consequences of the two wars of 1625 and 1672 between the Republic of Genoa and the Duchy of Savoy, during which the community was forced to provide food, wood and straw to the Savoy soldiers, who also forced the people of Bussana to exhausting field work to provide for their sustenance. These conflicts, however, do not seem to have caused serious damage to the structures of the village, which was further fortified by the construction of external walls of the outlying houses, used as walls in the event of an attack with weapons, an eventuality that would, however, never have occurred in the history of the village.

During the seventeenth century the territory of Bussana also had to suffer the consequences of the two wars of 1625 and 1672 between the Republic of Genoa and the Duchy of Savoy, during which the community was forced to provide food, wood and straw to the Savoy soldiers, who also forced the people of Bussana to exhausting field work to provide for their sustenance. These conflicts, however, do not seem to have caused serious damage to the structures of the village, which was further fortified by the construction of external walls of the outlying houses, used as walls in the event of an attack with weapons, an eventuality that would, however, never have occurred in the history of the village.

During the XVIII century also Bussana was involved in the war of Austrian Succession, in which the Republic of Genoa took part, having to endure in particular the frequent passages of French-Spanish troops, which however introduced two very important agricultural products that would later have had a considerable importance in the life of the villages of the Ligurian hinterland: tomatoes and potatoes, which were since then also cultivated by the farmers of Bussana with enormous advantages for the sustenance of the population, especially during periods of famine and drought.

Meanwhile, from nearby France, where many Bussanesei often went in search of work, revolutionary ideas began to spread even in the Far West, destined to upset the political and social life of western Liguria, as in the rest of Italy, when the spread of Jacobin ideology put the « l’ancien régime » in crisis and with it all the traditional structure of oligarchic power, leading to the fall of the ancient government and the establishment of the new Ligurian Republic in 1797.

Meanwhile, from nearby France, where many Bussanesei often went in search of work, revolutionary ideas began to spread even in the Far West, destined to upset the political and social life of western Liguria, as in the rest of Italy, when the spread of Jacobin ideology put the « l’ancien régime » in crisis and with it all the traditional structure of oligarchic power, leading to the fall of the ancient government and the establishment of the new Ligurian Republic in 1797.

Also in Bussana the effects of this revolution were felt and the local authorities, Consuls and Elders, were no longer democratically elected by the people, but imposed from above with the governmental appointment of the members of the Municipality.

After the annexation of Liguria to the French Empire in 1805, many young people from Bussana were called to arms to serve France in the various Napoleonic campaigns, so that many families were left without working arms, which at the time were indispensable for field work.

After the annexation of Liguria to the French Empire in 1805, many young people from Bussana were called to arms to serve France in the various Napoleonic campaigns, so that many families were left without working arms, which at the time were indispensable for field work.

From here the hostility against Napoleon grew, which manifested itself in all its fullness when, at the fall of the Emperor, Pope Pius VII, on his way back from Rome from Fontainebleau, received a triumphant welcome in Bussana with the population who competed to carry the Pope's sedan-chair, which, according to tradition, he would stop at Villa Spinola (then Lercari), where he was also offered a taste of the famous local muscatel wine.

From here the hostility against Napoleon grew, which manifested itself in all its fullness when, at the fall of the Emperor, Pope Pius VII, on his way back from Rome from Fontainebleau, received a triumphant welcome in Bussana with the population who competed to carry the Pope's sedan-chair, which, according to tradition, he would stop at Villa Spinola (then Lercari), where he was also offered a taste of the famous local muscatel wine.

The celebrations in honour of the pope denote, among other things, the disappointment and tiredness of the people towards the hopes nourished during the Napoleonic period, so much so that the fall of French domination, the brief restoration of the Republic of Genoa and the subsequent annexation of Liguria to the Kingdom of Sardinia in 1815 were welcomed with relief.

In the first decades of the nineteenth century also the Bussanese, who had remained closed for centuries within their narrow circle of walls, sought alternative sources of income by starting up wine and oil trades or by dedicating themselves to craft activities in the nearby cities of Provence.

This economic dynamism brought the population of Bussano to a fair level of prosperity, which had no precedent in the history of the country.

However, even in those years there were natural disasters such as the earthquake of 26 May 1831, which caused the collapse of 24 houses, the small church of Sant'Erasmo and the serious damage to the vault of the parish church, while fortunately there were no victims, but only two injured women. Another earthquake, although less violent than the previous one, struck the village on the night between 28 and 29 December 1854, when the last part of the tower fell on the castle and a part of the more solid one at the house of Marco Antonio Della Torre at the beginning of via Rocche, and a boy perished when a wall collapsed.

However, even in those years there were natural disasters such as the earthquake of 26 May 1831, which caused the collapse of 24 houses, the small church of Sant'Erasmo and the serious damage to the vault of the parish church, while fortunately there were no victims, but only two injured women. Another earthquake, although less violent than the previous one, struck the village on the night between 28 and 29 December 1854, when the last part of the tower fell on the castle and a part of the more solid one at the house of Marco Antonio Della Torre at the beginning of via Rocche, and a boy perished when a wall collapsed.

Also this time, however, the village quickly recovered from the consequences of the earthquake, as evidenced by the great work carried out to provide drinking water in the village and, a short time later, the construction of the cart road, which connected the village to the coastal road. This important public work, imposed and carried out by the Civil Engineers at the expense of the population of Bussana, would have brought many advantages in the following years, but at the time it created some discomfort because, until then, Bussana was connected with the other localities through the mule track of the Bauda towards the east (Pozzi-Taggia) and that of the Vallao towards the west (Valle Armea), Poggio and Sanremo), while with the construction of the new road the southern exit immediately became the main one serving not only those who owned land at the head of the Marine, but also all those who went out of the country, thus enhancing the neighboring land.

The simultaneous construction of the railway line and the further improvement of the coastal road, where the first public transport began to pass, opened up new connections with neighbouring countries, encouraging the movement of people and the increase in commercial activities.

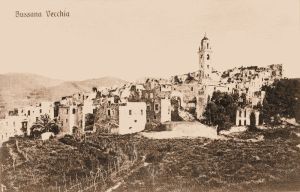

This phase of intense development had just begun, so positive and bringing renewed hope for the economic and social revival of the town that Bussana was hit hard by the catastrophic earthquake of 23 February 1887, which would change the history of the small town forever, laying the foundations for its reconstruction near the coast.

During the violent earthquake, whose first tremor occurred at 6.21 a.m., followed by another one at about 6.30 a.m., almost all the houses in the upper part of the village called "Rocche", which had already been severely tried in previous earthquakes, fell. Particularly damaging was the collapse of the walls of those near the only road leading from the church square to the upper part of the village, where the people who lived there were trapped and suffered serious losses as they found practically no way out.

During the violent earthquake, whose first tremor occurred at 6.21 a.m., followed by another one at about 6.30 a.m., almost all the houses in the upper part of the village called "Rocche", which had already been severely tried in previous earthquakes, fell. Particularly damaging was the collapse of the walls of those near the only road leading from the church square to the upper part of the village, where the people who lived there were trapped and suffered serious losses as they found practically no way out.

During the first tremor, as had happened in Baiardo, the vault of the church collapsed, where many faithful attended the religious services, but fortunately the vault resisted, albeit with serious damage, the first wave shock, so much so that the people, on the advice of the parish priest Don Francesco Lombardi who promptly shouted: "Save yourselves in the chapels!", had time to reach the side altars, which were protected by strong arches.

A few minutes after the second jolt caused the total collapse of the vault, which collapsed in a crash and overwhelmed the five people who remained among whom two girls managed to save themselves by sheltering under the sturdy benches. Even in the lower part of the village, from the church to the south, the district called "Fascette", many houses were damaged by the earthquake with falling ceilings and floors without however causing casualties among the inhabitants who fled quickly except for a woman who was killed by the rubble.

Very serious were instead the consequences of the third tremor, that of 8,51, shorter but more intense than the second, which killed some of the survivors who had returned to the village to try to rescue relatives who had remained closed in the "Rocche" and to recover clothing and food.

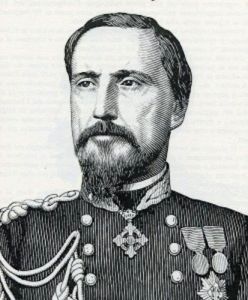

« Paradoxically, the greatest damage in Sanremo was not caused by the earthquake but by the earthquake after it. The State sent another Pinelli here, General Maurizio Gerbaix de Sonnaz, who gave very strict orders to shoot mercilessly at those who approached the rubble. Violent controversy between the local civil and religious authorities and the military: the former maintain that an attempt should be made to save those who have remained alive under the rubble, the latter declare that they want to defend the inhabitants from looting.

« Paradoxically, the greatest damage in Sanremo was not caused by the earthquake but by the earthquake after it. The State sent another Pinelli here, General Maurizio Gerbaix de Sonnaz, who gave very strict orders to shoot mercilessly at those who approached the rubble. Violent controversy between the local civil and religious authorities and the military: the former maintain that an attempt should be made to save those who have remained alive under the rubble, the latter declare that they want to defend the inhabitants from looting.

While the discussions are developing, some, at night, manage to draw from the rubble of Bussana, Bajardo and Diano Castello dozens of people still alive and are regularly shot at by merciless soldiers. It is certain that others remain, on the lower floors of the houses, under the vaults that have not collapsed, and for days and days waiting for help that will never come, and it is also certain - it must be shouted - that in the whole of Liguria not a single case of that looting that the General feared. De Sonnaz does not listen to reason, and he does not hesitate to say: "We will demolish these infamous hovels". And he begins by destroying the oldest part of the millenary Pigna, including the Church of San Costanzo, formerly San Pietro. Only the ever-higher protests of the adults succeeded in curbing the iconoclastic wrath, as a chronicler of the time wrote, but now the damage is done. The Pigna of Bishop Teodolfo, of the Saracens, of the first walls, the one that had resisted a thousand years of history and the avenging fury of Agostino Pinelli, is no more. Some traces can be recovered, if desired, under the earth brought to build the Regina Elena Gardens, which are not the pride of the city ».

(source: Giorgio Pistone in his book "Brief History of Sanremo")

The population of Bussana then lived for a few months under military tents and for about six years in wooden huts built in a flat area to the south-east of the village suffering all sorts of suffering and deprivation.

Remarkable and significant was also the solidarity shown by institutions and private individuals towards the Bussanese affected by the terrible earthquake, to whom 187 people and institutions sent clothes, blankets and money between 23 February and 15 July 1887. Among them were Andrea Podestà, General Stefano Canzio, the Municipalities of Genoa, Turin, Sestri Ponente, Serravalle, Novi Ligure, Acqui Terme, Vigevano, Voghera and various places as far away as Palermo and Alexandria, as well as the London Chamber of Commerce.

In the days immediately following the earthquake, the Prefect of Porto Maurizio Bermondi also promoted the establishment of a Provincial Committee for the collection of funds and materials for the countries most affected, including Bussana, which received a grant of 22,436 lire, while the total number of victims was finally, according to the official data of the Royal Commission, 54 dead (but perhaps two more) and 29 injured on a population of the country before the earthquake of 820 inhabitants.

In the following months the government also granted 66,899 lire to the Municipality of Bussana for the rehabilitation of the roads, 180,101 lire for the reconstruction of the municipal buildings, 12,700 lire for pious works, kindergartens, hospitals, shelters and hospices and 83,000 lire for other bodies, such as churches, oratories, canonical houses and confraternities.

Since the first days after the earthquake, doubts had arisen as to whether it would have been more convenient to repair the damage and rebuild many destroyed houses, or whether it would have been better to permanently abandon the old building and rebuild the whole village from scratch. After several surveys and heated discussions, the second division prevailed and so the government authorities imposed to the Bussanesi the abandonment of the old houses and the construction of the new ones in a well delimited area prepared by a special town planning plan, studied in detail by the Genoese engineer Salvatore Bruno, on the Capo Marine, two kilometres away towards the sea.

Thus, in the years between 1891 and 1894, Bussana Nuova was built, while the old village was definitively abandoned. In the same years in which the

Thus, in the years between 1891 and 1894, Bussana Nuova was built, while the old village was definitively abandoned. In the same years in which the  new village was being built, the construction of the Sanctuary of the Sacred Heart of Jesus also began, strongly and tenaciously desired by the parish priest Don Lombardi, which would be solemnly inaugurated in 1901.

new village was being built, the construction of the Sanctuary of the Sacred Heart of Jesus also began, strongly and tenaciously desired by the parish priest Don Lombardi, which would be solemnly inaugurated in 1901.

In the early years of the twentieth century the new village was therefore slowly getting back to normal, while many important public works, such as the school building and the pavements along the streets, had not yet been completed.

After the end of the First World War, which was attended by many Bussanesi who fell on the battlefields, the question of the autonomy of the town and its possible aggregation in Taggia rather than in Sanremo came up again and, in the end, the second hypothesis prevailed and Bussana, according to the provisions of Royal Decree no. 453 of 19 February 1928, was united to Sanremo becoming a fraction of the Municipality of Matuzia.

After the years of the fascist regime and the announcement of the armistice with the Allies, the town became an active centre of the resistance movement under the leadership of professors and cousins Giovanni Battista and Nilo Calvini, who availed themselves of the precious collaboration of numerous local anti-fascist exponents such as Emilio and Mario Mascia, Dr. Giovanni Pigati, Bruno Luppi, the lawyer Nino Bobba and Renato Negri, with whom several clandestine meetings took place, especially in Sanremo and Bussana in an old uninhabited building called "Villa Chiara", where the most important decisions were taken regarding the direction and coordination of the activity of the partisan groups in the area of Bussana.

After the years of the fascist regime and the announcement of the armistice with the Allies, the town became an active centre of the resistance movement under the leadership of professors and cousins Giovanni Battista and Nilo Calvini, who availed themselves of the precious collaboration of numerous local anti-fascist exponents such as Emilio and Mario Mascia, Dr. Giovanni Pigati, Bruno Luppi, the lawyer Nino Bobba and Renato Negri, with whom several clandestine meetings took place, especially in Sanremo and Bussana in an old uninhabited building called "Villa Chiara", where the most important decisions were taken regarding the direction and coordination of the activity of the partisan groups in the area of Bussana.

In 1944 the CLN of Bussana was also set up, which was made up of the shareholder Salvatore Alliotta, who assumed the role of president, the independent Alessandro Calvini, Nilo Calvini as military attaché, the communist Vittorio De Michele, the Christian Democrat Amedeo Podestà and the independent Paolo Rizzo. This committee would then take office in the Municipality on 25 April 1945, taking over the administrative direction of the town, to which Giovanni Battista Calvini also joined in September.

After the Second World War the town resumed its traditional activities based mainly on the floriculture and olive oil sector, while Bussana Vecchia was occupied in the early Fifties by a large group of Calabrian immigrants, who were forced to leave following the intervention of the public force, while the Municipality then dynamited the vaults of the houses in order to make them unusable forever.

About ten years later the well-known artist Clizia, after having seen the ancient village, decided to settle in the village together with about ten other artists, who gave themselves their own statute founding a real community, which in the following years would further grow thanks to the arrival of many artists from abroad.

About ten years later the well-known artist Clizia, after having seen the ancient village, decided to settle in the village together with about ten other artists, who gave themselves their own statute founding a real community, which in the following years would further grow thanks to the arrival of many artists from abroad.

In the meantime the small community acquired a wider and wider reputation, while the occupation of the ruins caused the reaction of many Bussanesi, who, after some attempts of eviction, were given priority to intervene on the upper part of the village, the most devastated area of the "Rocche", with the castle.

In 1967 the first workshop was opened in which it was possible to buy directly the works made by the artist, while the simultaneous arrival of new inhabitants determined the multiplication of the workshops and the sale of handicraft and artistic products. After the conquest of essential comforts such as drinking water, sewerage and electricity, in 1982 the Municipality of Sanremo launched an international competition to finally provide Bussana Vecchia with a detailed and rational urban plan that would allow its full recovery.

In 1967 the first workshop was opened in which it was possible to buy directly the works made by the artist, while the simultaneous arrival of new inhabitants determined the multiplication of the workshops and the sale of handicraft and artistic products. After the conquest of essential comforts such as drinking water, sewerage and electricity, in 1982 the Municipality of Sanremo launched an international competition to finally provide Bussana Vecchia with a detailed and rational urban plan that would allow its full recovery.

Although the town is still waiting for the realization of the winning plan, the old town is inhabited all year round by about fifty people of various nationalities, who during the summer season rise to two hundred, who have renovated about one hundred houses, where about thirty shops have been opened to display artistic products of the most varied nature such as paintings and sculptures, ceramics, costume jewellery, lithographs and numerous other artefacts made by valid artists, which have contributed to revive a dead city in a suggestive atmosphere, in which the active and enterprising spirit of the inhabitants of the ancient village seems to have risen from its millenary history. Unfortunately, despite the commitment of its inhabitants, who have practically rebuilt the village, the usual bureaucracy has committed itself to breaking the beautiful dream.

Unfortunately, despite the commitment of its inhabitants, who have practically rebuilt the village, the usual bureaucracy has committed itself to breaking the beautiful dream.

In 1984 the State Property Office says that the village is not a no-man's land, but a state land, and makes every previous cadastral inscription disappear in one fell swoop.

In 1999 the Minister of Cultural Heritage (Giovanna Melandri was there) defined the village as an "unavailable historical heritage". Like Pompeii. It seems like the farewell to every attempt at usucapioneering. Then, in 2017, it rains claims for the past years. A very hard blow.

The State beats the cash register: compensation was asked to those who occupied the buildings and the risk is that the houses will be auctioned anyway.

(sources: text by Andrea Gandolfo; images from private archive and web)

(last paragraph: Article Secolo XIX by Marco Menduini of 13 December 2019)