From the end of the Roman Empire to the Barbarian Invasions

There is not much evidence of the period from the end of the Roman Empire to the Saracen invasions. One can only speculate on episodes that are certainly not pleasant, given the passages of the various barbarian groups. The Visigoths of Alaric, for example, who in 401 crossed the whole Western Liguria to reach Gaul leaving behind them the destruction of Albenga and the damage caused to other villages encountered on their way. In the Vth century there were the raids from the sea by the Vandals of Genserico, and then others later by sea pirates.

There is not much evidence of the period from the end of the Roman Empire to the Saracen invasions. One can only speculate on episodes that are certainly not pleasant, given the passages of the various barbarian groups. The Visigoths of Alaric, for example, who in 401 crossed the whole Western Liguria to reach Gaul leaving behind them the destruction of Albenga and the damage caused to other villages encountered on their way. In the Vth century there were the raids from the sea by the Vandals of Genserico, and then others later by sea pirates.

After the end of the Western Roman Empire, the Byzantine one, in Liguria prepared a defensive organization suitable for the needs of the time, creating a series of fortified areas that in the far west went from Ventimiglia, Taggia and along the Argentina valley.

These ramparts  managed to resist the Lombard offensives from 569 to 643, but Rotari, king of the Longobards, in 643 was right in the Byzantine defences: Ventimiglia, still attested at the mouth of the Nervia, was completely destroyed, and it is assumed that the nearby villages suffered the same fate. From 774 the Longobards were succeeded by the Franks of Charlemagne, who occupied the Riviera until 888.

managed to resist the Lombard offensives from 569 to 643, but Rotari, king of the Longobards, in 643 was right in the Byzantine defences: Ventimiglia, still attested at the mouth of the Nervia, was completely destroyed, and it is assumed that the nearby villages suffered the same fate. From 774 the Longobards were succeeded by the Franks of Charlemagne, who occupied the Riviera until 888.

In the new order of the territory, the committees of Ventimiglia and Albenga continued to respect the boundaries of the Roman municipalities, generally coinciding with the ecclesiastical divisions of the dioceses subject to the bishops, which in the meantime had become primary centres of power. The hypothesis that the boundary between the dioceses of Ventimiglia and Albenga was along the course of the San Romolo stream (aqua Sancti Romuli) does not appear plausible since it would have divided the Matutian territory in half; the eastern boundary between the two committees was fixed, in documents dated 979-980 and later, at the Armea stream (Ab Armedanam usque ad Finar).

In the new order of the territory, the committees of Ventimiglia and Albenga continued to respect the boundaries of the Roman municipalities, generally coinciding with the ecclesiastical divisions of the dioceses subject to the bishops, which in the meantime had become primary centres of power. The hypothesis that the boundary between the dioceses of Ventimiglia and Albenga was along the course of the San Romolo stream (aqua Sancti Romuli) does not appear plausible since it would have divided the Matutian territory in half; the eastern boundary between the two committees was fixed, in documents dated 979-980 and later, at the Armea stream (Ab Armedanam usque ad Finar).

The bishops of Genoa extended and maintained their influence on the Villa Matuciana throughout the Early Middle Ages and this influence came from long before, thanks to knowledge between legend and reality. Religious tradition remembers that, at the end of the 5th century, the Bishop of Genoa, Felice (who later became a Saint) decided to send the deacon Siro to the Matuciana area, more to remove him from Genoa (he was becoming  too famous, with visions during ceremonies) than for spiritual reasons, ordering him to remain there until new orders. When he arrived at Villa Maticiana, Siro met Blessed Ormisda,

too famous, with visions during ceremonies) than for spiritual reasons, ordering him to remain there until new orders. When he arrived at Villa Maticiana, Siro met Blessed Ormisda,  vicar of Bishop Felice, whom he sent to the West to Christianise the population and then, through him, to subject him to the Genoese bishop, who then kept one of his chorepiscopus on site.

vicar of Bishop Felice, whom he sent to the West to Christianise the population and then, through him, to subject him to the Genoese bishop, who then kept one of his chorepiscopus on site.

During the time that he remained in the area, the deacon Siro, thanks to his real or presumed powers, received as a gift several plots of land, from the landowners of Matuzia and Ceriana, and also from a certain Gallione, tax collector of Taggia, for having exorcised his daughter, with vast tracts of land near the mouth of the river of Tabia (Argentina).

A strange thing was that, although the Matuciana area, from Capo Nero to the Armea torrent, was subject to the diocese of Ventimiglia, at first the parish church, the primitive church of San Siro and the castrum that later rose on the Pigna hill belonged to the diocese of Albenga. In reality, starting from the 6th century, as mentioned above, the inhabitants of Villa Matuciana were completely dependent on the Bishop of Genoa, who would maintain his temporal and spiritual jurisdiction over them.

The reasons for this singularity have been explained by Nino Lamboglia with the skilful political design of the Matuzians, maintained over the centuries, to « be independent, avoiding the nearest master to rely on the most distant and the least demanding ».

(The modification of the diocesan border only took place between 1315 and 1350, when it was moved to the west, on the Madonna della Ruota promontory between Bordighera and Ospedaletti, assigning the whole territory of San Romolo to the diocese of Albenga, an attribution maintained until 1831).  After Siro, the Genoese bishop Romolo, considered the apostle of evangelization in this part of Liguria, arrived in Matuziana land. There is no certainty about the period in which Romulus lived and worked; Jacopo da Varagine assigns Siro to 570 and Romulus immediately after, around 600. Having overcome numerous

After Siro, the Genoese bishop Romolo, considered the apostle of evangelization in this part of Liguria, arrived in Matuziana land. There is no certainty about the period in which Romulus lived and worked; Jacopo da Varagine assigns Siro to 570 and Romulus immediately after, around 600. Having overcome numerous  disputes, scholars have now agreed to place Romulus in the 7th century, and most believe he worked between the end of the 7th and the beginning of the 8th century AD.

disputes, scholars have now agreed to place Romulus in the 7th century, and most believe he worked between the end of the 7th and the beginning of the 8th century AD.

Almost everything and even nothing is known about Bishop Romulus. The Christian tradition, between legend and reality, wants him to be happy to stay at the Villa Maticiana because he preferred his tranquillity to the frenetic life in Genoa, so much so that he lived his years in a cave or "Bauma" at the foot of Monte Bignone where he lived in meditation, penance and prayer with a reputation for holiness and surrounded by general veneration and which, transformed into a chapel, became a pilgrimage destination for the many miracles that took place there. He died on 13th October of an unspecified year and his remains, after being made Blessed and then Saint, were moved to the crypt of the primitive Church of San Siro, near those of Blessed Ormisda. He later became protector and Patron of the City, so much so that over time, his name became an identification of the Villa Matuciana, which from about the tenth century was no longer so, replaced by the eleventh century by "Castrum Sancti Romuli", the urban agglomeration that in the rattempo rose on the hill of the Costa (La Pigna).

Without prejudice to these traditions, in reality Romulus' transfer was due to more political reasons, given the persecution to which the Church was subjected by the Longobards and,  as Girolamo Rossi mentions in his Storia di Sanremo, Romulus' isolation was due more to the mysticism between religious fervour and penance that was going through those times, leading the rest of Italy to create similar ones.

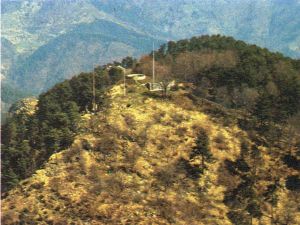

as Girolamo Rossi mentions in his Storia di Sanremo, Romulus' isolation was due more to the mysticism between religious fervour and penance that was going through those times, leading the rest of Italy to create similar ones. About then the real isolation of Romulus in the woods of Monte Bignone, Nino Lamboglia, archaeologist and scholar of the history of Sanremo, questions its authenticity, thanks to two documents of 979 which showed that in the area there must have been a castellaro

About then the real isolation of Romulus in the woods of Monte Bignone, Nino Lamboglia, archaeologist and scholar of the history of Sanremo, questions its authenticity, thanks to two documents of 979 which showed that in the area there must have been a castellaro  of ancient origin, perhaps the ancient Castellaro di Monte Bignone, then destroyed by the Saracens, who, like others between this and Mount Caggio, were frequented by families of shepherds and farmers. Therefore "not in a completely deserted wooded site, but in a quiet and secluded place, where living conditions and inhabitants of Roman descent already existed". This would also explain why the coastal populations found refuge there during the Saracen raids.

of ancient origin, perhaps the ancient Castellaro di Monte Bignone, then destroyed by the Saracens, who, like others between this and Mount Caggio, were frequented by families of shepherds and farmers. Therefore "not in a completely deserted wooded site, but in a quiet and secluded place, where living conditions and inhabitants of Roman descent already existed". This would also explain why the coastal populations found refuge there during the Saracen raids.

The Saracens

With this name were usually called the groups of Arabs dedicated to piracy and guerrilla warfare, who left from the North African and Spanish ports and with fast fleets carried out their raids among the populations of the coasts of the High Tyrrhenian Sea and the Ligurian Sea. In 838 a Saracen fleet formed by Arabs from Spain devastated the territory of Ventimiglia (it is not known if it also hit the Villa Matuciana, which grew up around San Siro). In 846 the same coast was hit again by Saracen raids in different points.

With this name were usually called the groups of Arabs dedicated to piracy and guerrilla warfare, who left from the North African and Spanish ports and with fast fleets carried out their raids among the populations of the coasts of the High Tyrrhenian Sea and the Ligurian Sea. In 838 a Saracen fleet formed by Arabs from Spain devastated the territory of Ventimiglia (it is not known if it also hit the Villa Matuciana, which grew up around San Siro). In 846 the same coast was hit again by Saracen raids in different points. In 899 a group of Arabs, coming from Spanish Andalusia, set up their headquarters at Frassineto, in the gulf of Saint-Tropez; in the following years, after having destroyed the surrounding towns, they started a long series of raids on the sea with the result, given their proximity, of subjecting the places on the coast to destruction, looting and kidnapping of women and men to be enslaved.

In 899 a group of Arabs, coming from Spanish Andalusia, set up their headquarters at Frassineto, in the gulf of Saint-Tropez; in the following years, after having destroyed the surrounding towns, they started a long series of raids on the sea with the result, given their proximity, of subjecting the places on the coast to destruction, looting and kidnapping of women and men to be enslaved.

By now the absolute masters of the territory, also considering the lack of an adequate political but above all military protection, the Saracens took real military actions investing the plains and the Piedmontese Alps, without however losing sight of the usual coastal raids, carried out by isolated gangs but continuing the operations of pillage, violence and also the outrage of churches and religious and the massacre of unarmed populations. Villa Matuciana suffered this fate several times; in 934, when Genoa was besieged, sacked and lost 5,000 men, many villages on the Riviera were devastated and burnt down. Previously, between 876 and 915, the mortal remains of St. Romulus had been moved to Genoa to prevent the Saracens from

Villa Matuciana suffered this fate several times; in 934, when Genoa was besieged, sacked and lost 5,000 men, many villages on the Riviera were devastated and burnt down. Previously, between 876 and 915, the mortal remains of St. Romulus had been moved to Genoa to prevent the Saracens from  outraging them; this fact, wanted by the Genoese bishop Sabatino, confirms once again the bishop's jurisdiction over the Matuzians.

outraging them; this fact, wanted by the Genoese bishop Sabatino, confirms once again the bishop's jurisdiction over the Matuzians.

After the betrayal of King Hugh of Arles, who in the summer of 942, on the point of defeating the Saracens, in a rivalry with Berengario of Ivrea, spared them and even charged them with occupying the Alpine passes to prevent the passage of enemy troops, the raids resumed undisturbed.

But in 950 Berengario II, who became King of Italy, reorganised the territory administratively (the committees of Ventimiglia and Albenga were assigned to the Arduinica and Aleramica brands respectively), and in 972 Guglielmo d'Arles, Count of Provence, finally promoted a military alliance between the feudal lords of Liguria and Provence, in which Guido of the Counts of Ventimiglia also participated.

After numerous battles, between 975 and 980 the Saracens were definitively defeated and the Lair of Frassineto conquered. A terrible century of devastation, pain and desolation had marked the existence of the coastal populations, who had abandoned the villages on the coast to take refuge in the hills and mountains of the interior, where they had rebuilt their villages, less exposed to danger, interrupting all economic activity and dedicating themselves to agriculture and pastoralism of pure survival.

Also the Matuzians had left their houses near San Siro to move to the mountain area of Bevino, between the Caggio and Bignone mountains, where Bishop Romolo had lived and died, and where we have seen some groups of rural houses already existed. The document of 980 says that the lands of San Romolo (Villa Matuciana) were made "deserted and sine habitatione relicte" because of the repeated Saracen actions.

Once the scourge ceased, people slowly resumed a normal life, returning to their usual residences and occupations. Everything had to be rebuilt: houses, work, commerce, relationships. In this huge plan of material and moral rebirth a decisive role was played by the monastic orders and the bishops, who distributed land to families, reorganized the work in the fields and resumed the education of the young people.

The will to regain a serene existence pushed the families to commit themselves to the reconstruction; in a short time the villages rose again, the countryside came back to life and life reaffirmed itself with all its vigour.

(Source: from the book "San Remo Storia e anima di una città", op.cit. Images from private archives and the Web)